My story: Why I believe in purposeful business

In 2008 I lost $80bn.

Twelve years earlier, I’d started what I thought was my dream job. In 1996 finance was big! Investment Banking was the place to make money, and being a trader was the pinnacle.

Images of champagne-drinking, Porsche-driving star traders were often on the TV in the 1980s. They had oversized mobile phones. They were surrounded by attractive girls with big hair and big shoulder pads. They were young successful and loaded with cash they’d made themselves.

In the 1980s I was living in Hartlepool. At the time a deprived Northern town with low wages, over 20% unemployment and lots of crime. Burglary and car theft were common as was vandalism, and if you were me, being beaten up weekly was the norm. There was a lot of poverty. One day at school two of my friends were reprimanded for breaking into the school the night before. They weren’t trying to steal cash or even the prized school video recorder. They’d headed straight for the ‘pig-swill’. They were hungry and knew that there was a ready supply of left-over food, easily accessible just inside the school grounds. My school didn’t perform well. I found out later it was one of the worst schools in the country with less than 10% of its pupils going to university.

I was lucky. My Dad was bright.

Although he’d left school at 16 to help my grandma with her ballroom dancing business, he studied accountancy in the evening. When he and my Mum had married, they’d moved to London, so Dad could go to accountancy college. During the day he worked as a trainee accountant for the London Borough of Waltham Forrest. My mum was a secretary in a sausage factory and had to order the raw materials that went into sausages and the skin that holds them together. When Dad qualified, they moved back to the Northeast. Dad got a job with the County Borough of Hartlepool. And there I was, getting beaten up at Manor Comprehensive with my pig-swill-eating friends and little prospect of higher education. A world away from the traders on the TV and constantly being told we didn’t have enough money to do things that I wanted to do. Go on holiday, get a better TV, or see a Wham concert!

I was lucky though, because when I was 13 my Accountant-Dad got his first commercial job at the Halifax Building Society, in Halifax. Only 95 miles away from Hartlepool, Halifax was a world of difference. Different accents, rolling hills, stone-built buildings and most importantly…

…..a state Grammar School.

I was also lucky because, like my Dad, I was also bright. I passed the entrance exams “with flying colours” and overnight my life changed. Crossley Heath Grammar was a domineering gothic-looking building, which started life as an orphanage in the 1600s. The kids wore blazers and had parents who worked at universities, the home office, ran big farms or were professionals.

“Crossley’s” went well for me. I was good at most subjects (except languages), and particularly good at numbers. I also liked science. My Physics teacher used to tell me to ask “Why?” to everything. “Never just accept what you’re told. Get people to prove things to you and if you’re not comfortable, just keep asking why. It would be over 20 years before I realised how important that was, but I took it to heart anyway.

I was also good at Economics. I loved it. The concept of Shareholder Value stood out for me. It just made sense. Look after the shareholders and the shareholders will look after everything else. Jobs will be created, and goods that people want will be produced. Markets will make sure there’s equilibrium and that makes everything fair. It seemed to make sense. It also seemed to be a route for me.

I decided to study business at university. For me, the obvious choice was to study in London. It looked like that’s where the businesses were. It was where people were making money and their lives looked better and more fun!

At University at King’s College London, I started to learn more about Finance, and I was good at it. I won the University Finance prize for a macro-economic study of the Japanese economy. Somehow I managed to predict the year-end close of the Nikkei that year within a few points. Of course, now I know that was a fluke but then, it felt great.

My prize was to visit the offices of Commercial Union opposite the Lloyds building. Visit the fund managers at their desks, talk about how they work and have a tapas lunch with them at Exmouth Market. I loved it. I was hooked!

By that time, the prize job that everyone on my university course wanted was to be an Investment Bank, “grad trainee”. At one point it felt like we were at a recruitment event every night. We went to the offices of either Goldman Sachs, Salomon Brothers, SG Warburg, Union Bank of Switzerland, Hambros, or Lehman Brothers. They were all the same! A speech by a Managing Director showing a big map of the world, talking about how much money the company made and demonstrating why they were going to be the “pre-eminent Investment Bank”. We ate our canapes and guzzled the free wine. We only wanted to know three things: How many (graduates), How much (money) and where was the “grad training”. What we wanted to hear was “Loads of grads”, “£30k+ starting salary” with “8 weeks of training in New York”. We’d compare notes in the bathrooms, mostly about the starting salary, which you had to pretend not to be interested in. We were frequently told "Don't worry about the starting salary. It’s nothing compared to what you can make in a few years." They were right!

Again, I was lucky. I got a graduate job, and I was thrilled. My family was proud, and my dad often told friends my starting salary, who were amazed (and a bit miffed) that it was making more than they made after 30+ years of hard work.

I remember having a pub lunch with my Mum, Dad, and Sister on one of those days. Chatting about the job I was about to start. Back in Halifax, in our local pub Investment Banking seemed like an alien planet.

I remember asking my Dad whether it mattered that Investment Banks didn’t create anything. Not only was there not a physical product but it wasn’t clear (to most people) what the benefit of an Investment Bank was. “Shouldn’t I do something that helps people?”, “something that has a result?”. In honesty, I expected a great answer from my Dad about how Investment Banks help insurance companies and pension funds make money for the policyholders and pensioners. In truth, I was HOPING my Dad was going to say this so I could justify my completely self-driven decision to go for a career that would generate a load of cash for me. It was to make me feel better.

He didn’t. He said it didn’t matter. As an accountant, he didn’t produce anything physical either and he was happy about that. He loved his profession and knew it was important and that was ok. That is ok.....Isn’t it?

I started at SBC Warburg on 1st July 1996. I’d asked to start earlier than the September intake because university finished in May, and I’d run out of money. I wasn’t on the trading floor. I was in something called Global Operations and Control. My starting salary was £25k and my training was in London, not New York, but it was good enough for me.

Because I started “early” no one was expecting me. I sat for three hours in a Human Resources meeting room, reading a physical staff handbook. It had phrases in it like “Due to the nature of the Investment Banking environment you may be expected to work outside of normal working hours”. That was fine with me, it further reassured me this was about working hard, playing hard and getting paid. That’s what I wanted!

Over the next 12 years, I got trained, got paid, got promoted and moved around the world.

I did get to New York. I lived there for two years and for another two years split my time between London and New York. I lived in Zurich for a year. Travelled regularly to India and Hong Kong.

The work I did was interesting, challenging and rewarding. I project managed an $800m acquisition of a corporate finance boutique in New York. I chose between multi-million-dollar systems to purchase in Zurich. Helped design, build, staff and run a 1,000-person processing centre in Hyderabad India and led a team in London that processed millions of trades a day transferring billions of almost every currency on the planet, to everywhere on the planet.

I loved it!

And then it all went pop. $80bn Pop!

On 14th February 2008, UBS announced an initial loss of $18bn, due to its subprime mortgage positions. UBS was the company that I was now an Executive Director of, resulting from various mergers. Over the coming months, the reported losses increased until UBS's losses totalled around $80bn. That was more money than the bank had made in the entire twelve years I’d worked there.

AIG reported a $500bn loss and Lehman Brothers Collapsed. In the UK RBS, The Halifax and Northern Rock collapsed and scenes that resembled a bank run were seen in UK High Streets. The global impact of the credit crisis, the global recession and nearly a decade of stinted global growth impacted billions of lives in ways that we can’t even imagine.

That day in 2008 wasn’t the end of my banking career. Far from it.

But that day I realised something wasn’t right. The credit crisis showed me that a focus on money alone doesn’t work. It didn’t benefit society or its people. In the end, it didn’t even make money. I started to think about business differently and how something more fundamental than money should drive business.

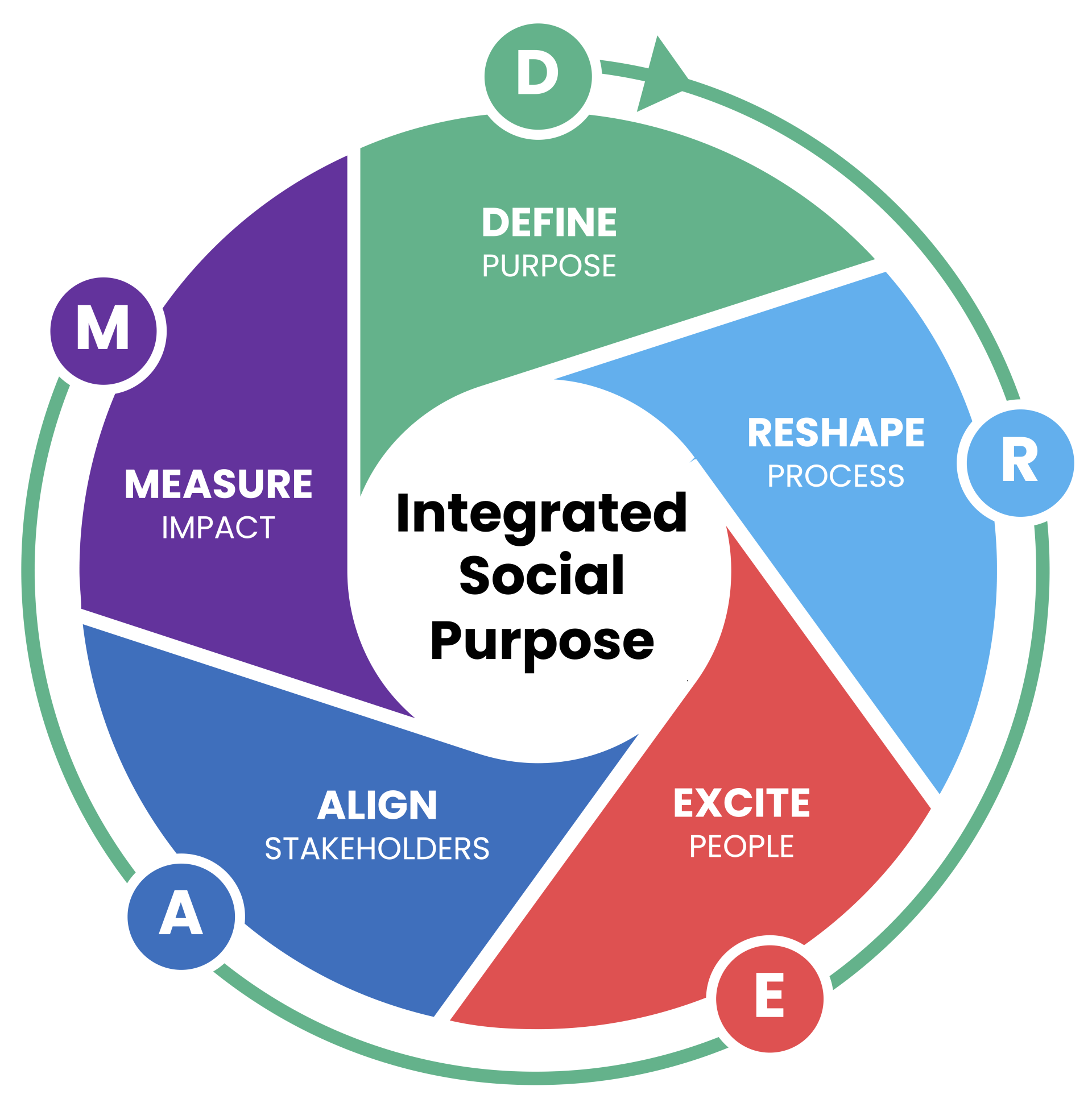

Over the following years, I worked out that the missing piece was social purpose. Over those years my experience and research led to Purposefully Business and the DREAM business method. Now, by using the DREAM business method businesses create more impact, greater engagement and faster growth, every day.